Flags at the Riverton Yacht Club

by Roger Prichard

On our pier, the flagpole and its flags are often the first things to catch your eye when arriving at the club, whether by land or water. The flags immediately tell sailors the two most important things for the day - how much wind is there and which way is it blowing?

The flagpole at any yacht club traditionally represents the mast of a sailing ship. The etiquette of which flag is flown, and onto which halyard it is bent, is one descended from centuries of tradition.

Until recent times, flags were the only way vessels could communicate with each other at sea. Lives and property often depended on understanding their protocols.

Even in the old days, recreational sailing's use of flags was more of a custom and seldom of critical importance. In those times, a breach of flag etiquette would raise eyebrows, but because today those customs are largely forgotten it can be fun to revive them. Following the old ways has its own charm and helps us continue the spirit of generations of sailors, great and not-so-great, who preceded us.

Because maritime flag etiquette is now often misunderstood by the public – and by some sailors – here are a few basic subjects which might be of interest:

Why isn't the US flag at the top? So what is the pennant at the top? What is the flagpole's history? Storm signals Flags on sailboats Flags on commercial vessels Why isn't the US flag at the top?

This is the most common question, a misunderstanding because the maritime tradition is so different from the land-side protocol.A yacht club is traditionally considered to be a vessel, not a part of the land. While land-bound tradition (and the U.S. Code) holds that no flag is to be higher than the national flag, this is not the case with vessels nor the related facilities of yacht clubs, harbormasters' offices, etc.

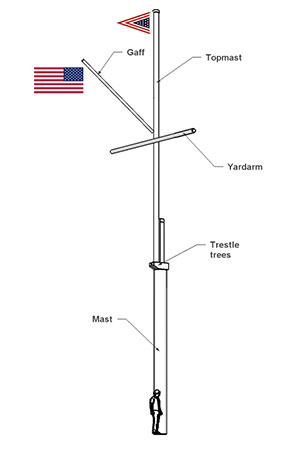

On a sailing vessel, the national flag of the ship's registry (called the "ensign") is traditionally flown from the outer end of the vessel's aftermost gaff. The gaff is the spar which supports the top of a gaff-rigged sail (those trapezoidal sails now seldom seen outside of old movies and on traditional craft). The end of the gaff is called the "peak", while the top of the mast, usually a round wooden disc, is called the "truck".

Many yacht club practices are firmly rooted in naval traditions. Here, the protocol is unequivocal, from an authority no less than the U.S. Navy. Per the chapter "Display of the National Ensign at U.S. Naval Shore Activities", in NTB 13 (B) 801. b. (4) "Polemast with Crosstree and Gaff – This is commonly called a 'yacht club mast'. Displayed from gaff."

A fine discussion of the inseparable traditions of the navies and yacht clubs is found at the United States Power Squadron's website. After consultation with the Coast Guard, Coast Guard Auxiliary and the New York Yacht Club they summarized: "The gaff of a yacht-club-type flagpole is the highest point of honor, as is the gaff of the gaff-rigged vessel it simulates. The U.S. ensign alone is flown there. Although another flag may appear higher (at the truck of the mast), no flag is ever flown above the national ensign on the same halyard (except the worship pennant on naval ships)."

From time to time, unfortunately, offense is taken by some who have not troubled to learn the facts. The Power Squadron website relates that the Palm Coast Yacht Club had a "continuing battle" with a local veterans' group over just this issue, settled only when the Secretary of the Navy (!) was obliged to write a letter confirming the fact that in the world of yacht clubs, the highest point on the mast is not, in this case, the place of greatest honor.

More background on the this and other traditions of flags on yacht clubs is interesting reading. See the classic texts "Annapolis Book of Seamanship" by John Rousmaniere, "Chapman Piloting & Seamanship" by Charles B. Husick, and "Yachting Customs and Courtesies" by James A. Tringali.

But setting aside misunderstandings and perceived insults, the obvious question really is, why from the gaff? We can't know for sure, but it seems reasonable that since identifying the nationality of a ship from a distance was critical in wartime, the ensign needed to be large and to stream free, avoiding fouling in the rigging. This spar was also less likely to be shot away in an engagement, or carried away in a storm, as the top of any mast might be.

This is clear in this engraving of a ship contemporary with RYC's founding: a U.S. Navy ship-of-the-line, from the 1848 edition of "The Kedge-Anchor; or Young Sailors' Assistant" by William Brady, Sailing Master, USN. The ensign is flying clear and unimpeded from the gaff on the mizzen (the aft, or rear-most) mast, while other signals are displayed from the masthead and jackstaff.

If you've ever visited the USS Constitution in Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, you'll have seen that Old Ironsides flies the ensign properly, too. In fact, most modern US Navy vessels, when underway, fly the ensign from a small steel gaff up on the superstructure of the ship. (In general, though, other steamships and their successors use a different set of rules.)

Are there exceptions? Naturally – there were regional and personal variations. Some artwork from the colonial era shows naval vessels flying the ensign in various places. Whether the captains actually displayed the flags that way or whether this was based on the imagination of an artist many miles away is open to question.

Today, a few vessels in the Maine schooner fleet, all of which are gaff-rigged, have given up and now fly the ensign from the highest mast, having grown weary of members of the public taking offense at what is indisputably the correct protocol.

So what is the pennant at the top?

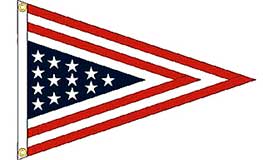

This is the "burgee" and it is each yacht club's own, unique symbol or logo. Traditionally, the burgee is a way for sailors to identify boats of their own club when away from home. Only members of a club are permitted to fly its burgee.

Riverton Yacht Club's burgee dates from the club's founding in July of 1865, and tradition holds that the similarities to the US flag reflected the patriotism which ran high in the immediate aftermath of Lincoln's assassination and the end of the Civil War.

Some early photos show RYC's burgee as a swallowtail, rather than a pennant.

What is the flagpole's history?

The RYC flagpole is a historical treasure – and a mystery. The mast and topmast of the RYC flagpole once sailed far as part of the rig of a sailing vessel of considerable size, probably a schooner. So not only does this flagpole represent the mast of a ship, it actually is the mast of a ship! Unfortunately, that tantalizing bit from the golden age of sail is all we know about its history. No one alive today knows when the club obtained the spars, nor from which vessel.

The mast is actually in two parts: the mast and the topmast. Over time, the mast itself (the lower part) has been cut down, undoubtedly for safety. Early 20th Century photos of the club show the mast as much taller and apparently unsupported by stays or shrouds as it would have been on a ship. Considering the force of the wind on this pier during storms, it's remarkable that the original, tall rig survived as long as it did. As it is, the masthead is about 60' above the deck of the pier and the top bends noticeably in strong winds. After being shortened, the proportions are now unlike they would be on a ship, where the spars generally get shorter the higher they are.

The topmast partially overlaps the mast itself, supported on two short timbers called "trestle trees". A heavy square wooden pin rests on these supports, driven through the square mortise hole in the bottom of the topmast.

Townsend Wentz prepares the topmast for lowering, October 2003.

This design was standard on all large sailing ships. It not only allowed a taller mast to be made from smaller logs, it also made a ship at sea more self-reliant. If the rig were damaged, the crew wouldn't need a crane to lower any of the higher spars for repairs or replacement, merely using a block and tackle and a capstan (or a lot of muscle). The first upper spar, as at Riverton, is called the "topmast". Larger square-rigged ships went far beyond that, with higher "topgallant" and "royal" masts not uncommon. The barkentine Gazela, berthed at Penn's Landing, has three spars on her foremast: the mast, the topmast and the topgallant (the latter pronounced something like "t'gallnt"). Gazela's crew generally lowers all the upper spars for the winter. USS Constitution is also similarly laid up for winter, with all the upper spars brought down on deck.

The upper spars could also be lowered as heavy weather approached, to bring the center of gravity of the whole rig lower. This would help keep the ship from rolling dangerously in heavy seas. This exercise was called "housing" the upper masts and an experienced crew could do this quickly, even in bad weather.

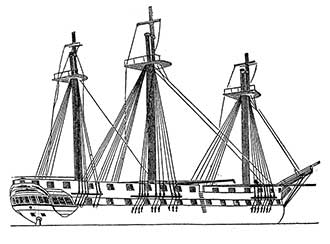

This engraving, also from "The Kedge Anchor", shows a frigate with her topmasts housed.

In more recent history, upper masts were also housed to clear bridges – a practice you can still see here today. Delaware's tall ship Kalmar Nyckel, a replica of the first Swedish ship to colonize the area, berths in the Christina River in Wilmington. To reach her wharf, she must pass under the I-495 bridge and her crew lowers her topmasts to clear it.

At Riverton we have lowered the topmast for painting and repair in recent years. Over the winter of 2003-2004 we repaired a considerable split in the topmast which was beginning to rot, gluing in a new "dutchman" of sound Douglas fir to replace the rotted area. National Casein kindly donated the epoxy for this project.

While the history of the mast itself is unknown, the other two parts, the gaff and yard, are more recent – and even quirkier. Both owe their existence to the RYC tradition of making things last and never discarding something which still may be useful. The present gaff is actually a carbon fiber windsurfer mast, installed in 2007 to replace a similarly re-purposed spar, an old boom from a Comet-class sloop, which broke the year before, having served as the club gaff for many years after its retirement from who knows how many racing seasons.

The yardarm appears to be part of a mast from a Lightning-class sailboat of unknown origin. Together, the gaff and yard are smaller than would be found on an actual ship's mast, and are mounted very differently.

The weathervane at the top brings a pedigree, having been constructed by long-time member Howard Lippincott. It is soundly made of stainless steel and bronze, and is about three feet long. It is perfectly balanced and pivots on its bearing in the slightest breeze. Howard Lippincott was an honorary life member of RYC (and its oldest member) when he passed away in 2005 at the age of 85, a skilled yacht builder whose Lippincott Boat Works just inside the mouth of the Pompeston Creek turned out champion Stars and Lightnings year after year. He held a number of national and international sailing titles himself.

Roger Prichard fairs in a new piece of wood on the topmast, April 2004

Storm Signals

The expression "storm warnings" is still in common-enough usage today, but who ever sees them in use? At RYC, we try to keep this tradition alive in an informal way.

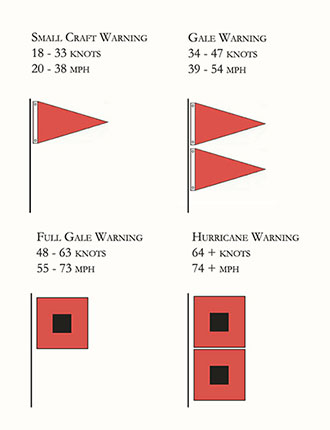

Before radio, flag signals were one of the common means of warning mariners not to venture out onto the open water when heavy weather was predicted. Flown from coast guard bases, lighthouses, and the like, a variety of shapes and colors were used at different times, indicating not only the expected strength of the wind but also the compass direction from which the storm was approaching.

At Riverton Yacht Club, we have revived the tradition of displaying the appropriate daytime flags, based on the NOAA marine forecast for upper Delaware Bay and local conditions as it seems appropriate. We use the convention once followed by the National Weather Service, which discontinued the use of flags in 1989 but has attempted to reinstate their use from time to time. Ours is only a volunteer effort, so don't assume the lack of a flag means no storm is due!

Flags on sailboats

Riverton is home to recreational craft and our boats are most often seen underway during the weekly races on Wednesday evenings and some Sunday afternoons. It may seem peculiar that none of them are flying flags at all. This is actually in accordance with the rules, which bar all flags while racing (including the national ensign). The reason for this is that racing boats do use a few important signals to communicate special situations, protests, etc. to the race committee and the fewer opportunities for error on the race course the better.

Other than while racing, there are traditional ways of flying flags, though variations abound.

Historically, say for the first 50 years of RYC's existence when all our fleet were gaff-rigged, the same rule about the national ensign was followed on a yacht just as it is on a frigate: it flies from the aftermost gaff. And just like on the club flagpole, the skipper's yacht club burgee flies from the head of the main mast. On a boat with multiple masts, such as a schooner or ketch, the owner's "private signal" flies from the head of a mast other than the main. The private signal was a flag or pennant of a design unique to the owner or family, usually with colors and symbols of personal meaning, a sort of individual logo.

For a full set of drawings of how to fly your many flags in the age when yachting meant polished brass (and a crew who polished it for you when they weren't bringing you sherry and hors d'oeuvres) see the July 1916 issue of the Rudder Magazine.

Even more pomp and ceremony of a by-gone age can be found in the "Yachtsman's Handbook" of 1912. On page 210 is a delightful array of rules of etiquette from the New York Yacht Club's rulebook, straight from the era of the Titanic. If you ever wondered how to indicate that the crew is at dinner, or felt unsure when it was proper to fire a saluting cannon …

The rules for modern sailboats are far easier to follow. Since few boats have gaffs, the most traditional way of flying the ensign is from the leech of the aftermost sail or from a backstay, at about the same height as the peak of a gaff would have been. More commonly, and thankfully much simpler, the ensign can now fly from a small staff mounted on the rail at the stern of the boat, as it does on a powerboat.

The club burgee flies from the boat's main masthead, or actually from above the masthead on a small flagstaff which goes up with the flag (usually called a "pig-stick").

An old custom which is still easy to follow is to "dress ship" for festive occasions. This is often seen at traditional craft festivals, when naval vessels are being commissioned, and on holidays. A whole set of signal flags is tied together and run up to the mastheads, giving even the most fearsome warship a rakish giddiness. It's generally the only way the full alphabet (and more) of signal flags is used today, which is reason enough to do it. Some boating suppliers still sell whole sets of signal flags for the purpose.

Flags on Commercial Vessels

While no large vessels still pass Riverton under sail (excepting New Jersey's tall ship the AJ Meerwald on her annual visits to Burlington), the diesel tugs and huge bulk carriers on the river follow today's formal flag rules scrupulously. Here are some of the flags you may see passing us:

Ensign: Tugs generally follow the sailboat tradition of flying the national flag from a small gaff, usually high on the superstructure aft of the stack. This may be partly tradition, but it also has the very practical advantage of keeping the aft deck of the tug clear of obstructions to the towing hawser. Larger freighters inevitably carry their ensigns from a staff on the stern rail (interestingly, the lowest point on the vessel!). Look closely and you'll see flags from all over the world pass us on the river. The fact that many of these vessels have never visited their country of registry just adds a bit of irony to these traditions.

Courtesy Flag: Foreign-flagged vessels will always fly the United States flag from a halyard high up on the starboard side of the superstructure. This is not only a formal courtesy of recognizing they are in US waters, it indicates that the vessel has cleared customs and so is here legally. Foreign sailboats, such as all the Canadian "snowbirds" who transit the lower Delaware and the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal each winter, will all be seen flying the US flag from the starboard spreader of the mainmast.

Quarantine: When a foreign-flagged vessel has entered US waters but before it has cleared customs it requests clearance (called "pratique") by flying the yellow international "Q" ("quarantine") signal flag from the starboard halyard where the courtesy flag will replace it. Ships reaching Riverton have cleared, but you will sometimes see ships below the Walt Whitman Bridge still flying the "Q".

Pilot flag: Most large vessels passing us will be flying a rectangular red and white flag, the international "H". This indicates that the vessel is under the command of a licensed river pilot. All vessels above a certain size on the Delaware River are required to carry a pilot who is licensed and knowledgeable about the local waters. He or she is responsible for the safe passage of the ship.House flag: Similar to the yacht club burgee, every shipping company has its own "house flag", usually the logo of the fleet, often bearing the same colors or design as is painted on the stack of the ship. Some of these are steeped in tradition and go back a century or more. There were once thousands of these, registered with Lloyds of London. A modern house flag you'll likely see passing Riverton is that of the Vane Brothers Company of Baltimore, which operates a fleet of tugs on the Delaware. Their swallowtail flag includes their company colors and the initial "V".